Ich habe dieses Buch gelesen, weil ich die Besprechung von The Economist (siehe gelb markierte Stelle) nicht richtig gelesen hatte. Ich bezog irrtümlicherweise den letzten markierten Satz auf «The Glass Hotel», anstatt auf «Station Eleven». Bei der Lektüre enttäuschte mich zunächst zunehmend der überhaupt nicht vorhandene Bezug auf die «pandemic that devastates the Earth’s population». «Station Eleven». bleibt somit auf der ‚to read‘-Liste.

«The Glass Hotel» verstört. Das Buch mäandert eher zufällig, beliebig, jedenfalls ohne erkennbaren roten Faden zwischen verschiedenen Handlungssträngen, Zeitebenen, Bewusstseinsebenen und wesentlichen gesellschaftlichen Fragen hin und her. Die Geschichte beginnt im äussersten Norden von Vancouver Island, in einem surrealen Luxushotel im Niemandsland, das dem Financier Alkaitis gehört. Am Ende verläuft sie sich in einem anderen, ebenfalls surrealen spirituellen Niemandsland. Dazwischen werden Drogen genossen, Beziehungen aus dem Nichts aufgenommen, kommt der Bernie-Madoff-Klon Alkaitis mit seinem Ponzi Scheme zu sagenhaftem Erfolg, und zum abrupten Sturz vom absoluten High der New Yorker Gesellschaft ins Gefängnis, und seine Show-off-Frau (unverheiratet), ehemals Barmaid in Alkaitis ‚Ausstiegs‘-Spielzeug auf Vancouver Island, verschwindet spurlos aus dem New Yorker Bohème-Milieu (Künstler, Galeristen, Cocktail-, und Small Talk- und ‚luxury-shopping-as-a-duty-and-full-time-occupation‘-Gesellschaft). Sie taucht wieder auf, zuerst als Hilfskoch auf einem Giga-Containerfrachter, und schliesslich unter beim waghalsigen Videofilmen über die Reling des Frachters im Sturm im Atlantik.

Und eher beiläufig, zwischen den Zeilen, wird die Frage beantwortet: Kann der Mensch der Strafe für ein Verbrechen, für seine Taten und Unterlassungen, je entkommen?

Das Buch ist gut, sec und süffig geschrieben; die freie Struktur, um nicht zu sagen die Strukturlosigkeit, gehört offenbar in unsere Zeit, ist für mich aber gewöhnungsbedürftig.

Besprechung des Buchs in The Economist, March 28, 2020

Books and Art – Disappearing acts – Women overboard – People – and money – vanish in «The Glass Hotel»:

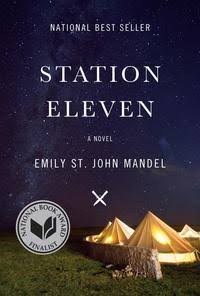

The author of «Station Eleven» tells a tale of Ponzi schemes and haunting pasts. «The Fatal Eggs» is a parable of bureaucratic bungling and drastic countermeasures.

The Glass Hotel. By Emily St. John Mandel. Knopf; 320 pages; $26.95; Picador; £6.99.

After producing three respectable thrillers, the Canadian author Emily St John Mandel raised her profile with her boldly inventive fourth novel. «Station Eleven» (2014) tells of a flu pandemic that devastates the Earth’s population, and follows a group of travelling Shakespearean actors who perform for the survivors 20 years later. The narrative’s before-and-after structure beautifully balances the life and death of a single individual against the fate of civilisation. Beyond its grim dystopia, the story hints at a brave new world founded on hope and humanity.

Today, «Station Eleven» is as timely as a novel can be. Ms Mandel’s new book, «The Glass Hotel», partly revolves around another catastrophe, only this one is financial and hope is more elusive. Swapping the post-apocalyptic future for the recent past, and charting the chequered fates of a wide cast of characters, she spins a beguiling tale about skewed morals, reckless lives and necessary means of escape.

The main protagonist is Vincent, a young (female) bartender at a swish hotel on Vancouver Island who had a tragic childhood. One night a vicious anonymous message is scrawled on the building: «Why don’t you swallow broken glass?» One of the guests, a shipping executive named Leon Prevant, is disturbed by the graffiti. Vincent herself is shocked and contemplates fleeing, even disappearing. Instead, after serving drinks to the hotel’s owner, Jonathan Alkaitis, she seizes an opportunity and elopes with him to New York.

There she adjusts to her new role as a trophy wife in «the kingdom of money». Alas, all that glitters turns out to have been fraudulently acquired. Alkaitis is running a multibillion-dollar Ponzi scheme reminiscent of Bernie Madoff’s; its collapse wipes out fortunes and forces Vincent to start afresh, this time as a cook on a container ship. But while at sea she disappears overboard. Leon, one of many investors ruined by Alkaitis, is charged with solving the mystery. Did Vincent fall or was she pushed? And has she washed up on another shore ready to reinvent herself again?

«The Glass Hotel» is a sprawling, immersive book. In places it is disorientating, as the narrative chops between timelines and perspectives. Minor characters, such as Vincent’s half-brother, drift in and out. And yet the novel’s scope and brimming vitality are also its strengths. Vincent’s encounters with the plutocracy are memorably realised; so are Alkaitis’s concoction of a ‚counterlife‘ in his prison cell and his employees’ struggles to save their skins.

In the end, all the stories are drawn together by a single question: can you ever escape what you have done in the past, and what has been done to you? «There are so many ways to haunt a person,» the author writes, «or a life.»